Anführungszeichen? Dazu soll es genug für einen ganzen Beitrag zu sagen geben?

Wir haben alle im Englischunterricht gelernt, wie man im Englischen Anführungszeichen setzt: oben (nicht unten) am Anfang und oben am Ende des gesprochenen Textes.

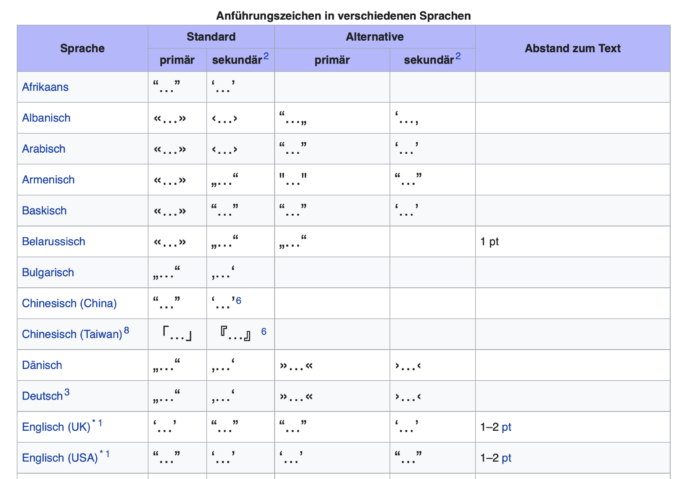

Aber es gibt auch noch ein paar weitere interessante Aspekte. Laut Wikipedia werden im UK-Englisch “einfache” Anführungszeichen gesetzt (‘Oh!’, he said), während doppelte Anführungszeichen für ein Zitat innerhalb eines Zitats benutzt werden.

Als Beispiel dazu dient der folgende Dialog zwischen Prof. Dumbledore und dem jungen Tom Riddle (aka Lord Voldemort).

Riddle gave an irritable twitch, as though trying to displace an irksome fly.

‘You dislike the name “Tom”?’

‘There are a lot of Toms,’ muttered Riddle. Then, as though he could not suppress the question, as though it burst from him in spite of himself, he asked, ‘Was my father a wizard? He was called Tom Riddle too, they’ve told me.’

‘I’m afraid I don’t know,’ said Dumbledore, his voice gentle.

J. K. Rowling: Harry Potter and the Half-blood Prince

In diesem Beispiel sehen wir, dass im britischen Englisch einfache Anführungszeichen benutzt werden und für das Zitat im Zitat (sogenannte sekundäre Anführungszeichen) doppelte.

‘You dislike the name “Tom”?’

J. K. Rowling: Harry Potter and the Half-blood Prince

Das folgende Beispiel aus Jurassic Park zeigt Anführungszeichen im amerikanischen Englisch (primäre Anführungszeichen doppelt, sekundäre einfach).

“Hey,” she said, more brightly. “According to this book, ‘the beaches of Cabo Blanco are frequented by a variety of wildlife, including howler and white-faced monkeys, three-toed sloths, and coatimundis.’ You think we’ll see a three-toed sloth, Dad?”

Michael Crichton; Jurassic Park

Ein weiteres Beispiel aus Jurassic Park zeigt eine weitere Eigenheit des angelsächsischen Gebrauchs von Anführungszeichen. Wenn eine Person spricht, und das Gesprochene im anschließenden Absatz fortgeführt wird, fehlen im ersten Absatz die schließenden Anführungszeichen, im folgenden Absatz werden sie gesetzt, um zu signalisieren, dass der Sprecher weiterhin spricht. Dies sieht man so im Deutschen nicht.

“Nobody knows. And the Hoods are even more worrisome,” Morris continued. “Hoods are automated gene sequencers-machines that work out the genetic code by themselves. They’re so new that they haven’t been put on the restricted lists yet. But any genetic engineering lab is likely to have one, if it can afford the half-million-dollar price tag.” He flipped through his notes. “Well, it seems InGen shipped twenty-four Hood sequencers to their island in Costa Rica.

“Again, they said it was a transfer within divisions and not an export,” Morris said. “There wasn’t much that OTT could do. They’re not officially concerned with use. But InGen was obviously setting up one of the most powerful genetic engineering facilities in the world in an obscure Central American country. A country with no regulations. That kind of thing has happened before.”

Michael Crichton; Jurassic Park

Der Vollständigkeit halber hier noch ein weiterer Unterschied in der Zeichensetzung zwischen dem Deutschen und dem Englischen.

‘I … oh … very well,’ said the Prime Minister weakly. ‘Yes, I’ll see Fudge.’

J. K. Rowling: Harry Potter and the Half-blood Prince

Im Englischen kommt zunächst das Satzzeichen, das den Halbsatz abschließt (also z. B. ein Komma) gefolgt vom Anführungszeichen. Im Deutschen ist es umgekehrt. Am Satzende gilt in beiden Sprachen 1. das Gesprochene 2. Punkt 3. Anführungszeichen.

»Ich … oh … nun gut«, sagte der Premierminister matt. »Einverstanden, ich werde Fudge empfangen.«

J. K. Rowling: Harry Potter und der Halbblutprinz

Schreiben Sie einen Kommentar